“Racing is life. Everything else is waiting…” –Steve McQueen

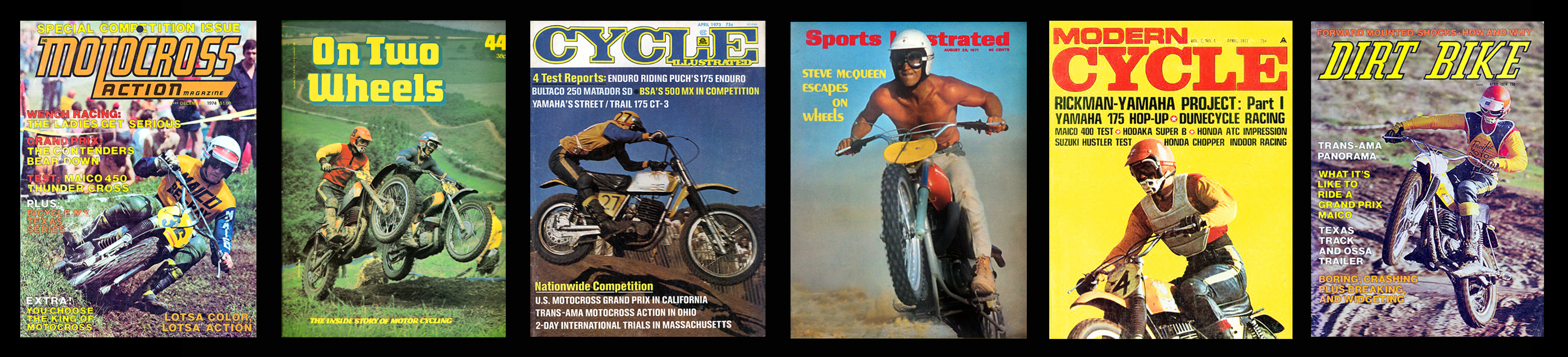

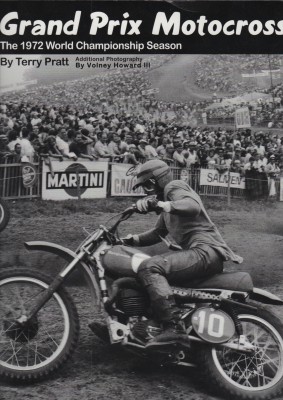

The 1970’s were the golden age of motocross. It was the peak of one era, and the beginning of another. What began many years earlier as a sport where former WWII couriers showcased their cross country skills on motorcycles grew to become a sensation. Even in the height of the Cold War, an international arena appeared for these intense competitions between individuals, manufacturers, and countries vying for the newly created Motocross Grand Prix World Championship.

Originally the motorcycles were modified street bikes, very heavy, and under-suspended. The bikes were ridden mostly in the style of street machines, but over jumps and rough and highly varied terrain in cross country, or Hare Scrambles, and in the case of motocross, on closed tracks.

It was a sport that required the utmost in strength, skill, and conditioning, and a lot of strategy. In Europe, manufacturers and star riders drew crowds of 50,000 people regularly to the GP events. Besides the mechanical difficulties inherent in the punishing sport, weather, the track, and the crowd could contribute to the never-certain outcomes of races.

It was a sport that required the utmost in strength, skill, and conditioning, and a lot of strategy. In Europe, manufacturers and star riders drew crowds of 50,000 people regularly to the GP events. Besides the mechanical difficulties inherent in the punishing sport, weather, the track, and the crowd could contribute to the never-certain outcomes of races.

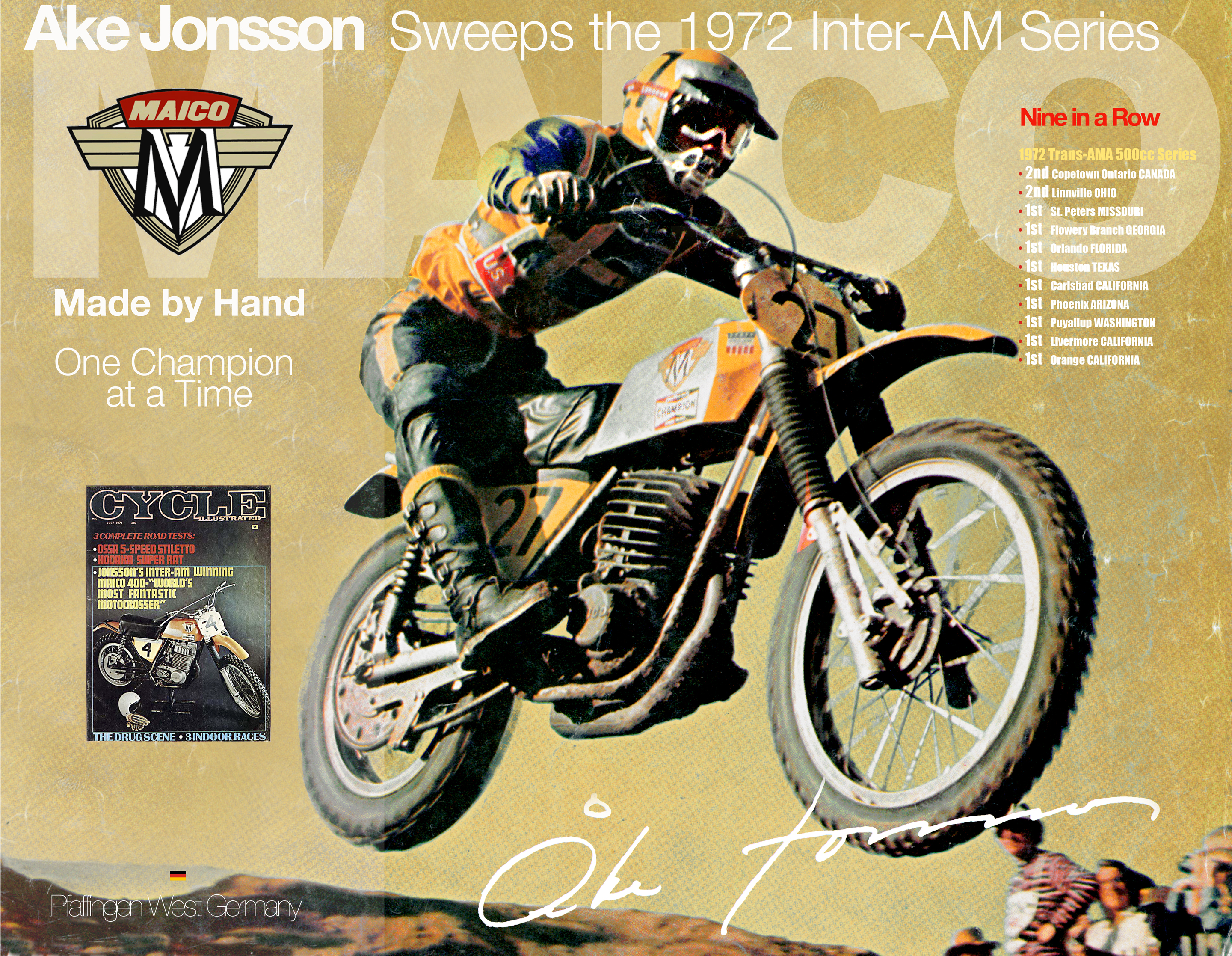

In the early ’70’s Japan entered the arena with their brilliant one-off factory racers that gathered the best design assets of the European bikes and improved on them. Back then there were as many as 40 manufacturers vying for the Championship. Even Harley Davidson and Ducati were contenders. The Europeans had created the sport and were accustomed to slowly developing their racing technology year by year with bikes built by hand. When the Japanese entered the game with their large budgets, R&D and manufacturing capacities, things changed. Soon the old guard was being challenged on their own turf, and the sport exploded into the fastest growing and most competitive in the world.

The United States was a playground for the seasoned European pros who came here to do exhibition races in the ’60’s. But it wasn’t long before thousands of green young Americans were inspired to compete in this spectacular sport. It has been said that in Europe, Motocross was as graceful and strategic as bull fighting.

But in America, motocross was as wild as bronco busting.

One of the changes that developed in this competitive environment was the lengthening of suspension. The introduction of the mono-shock by Yamaha in 1973 heralded the end of the twin-shock era, and the beginning of what is known today as the Evolution era. The bikes became taller and were ridden differently, and the tracks changed to accommodate the new range of abilities in handling and power.

In 1973 I purchased my first true love; the hand-made West German Maico. After carrying it behind me broken for 30 years I still have the bike today. Restoring it was my extended mid-life crisis project. By then, the small Pffafingen factory had closed down, and I wondered if I would ever be able to find parts again for the old soldier.

Twenty years ago, the American Motorcycle Association created a league where us old guys could race the old iron again; the American Historic Motorcycle Racing Association (AHRMA). Today the sport of vintage motocross flourishes again on tracks all over the world that are suited to the older bikes’ abilities. Parts are traded and sold on the internet and at swap meets, some are even being remanufactured or fabricated by individuals who keep the old bikes running. There is even a National Championship.

Forty four years later, the Maico is a living fossil among racers, but one of the most sought after around the world.

Today my son is the perfect size and weight for the bike. As he rides it, the fields tremble once again under the howl of racing engines. There is nothing else like it. The wick is lit, and the torch is passed.